MIXMAG IS 40: AN INTERVIEW WITH OUR FIRST EVER COVER STAR, SHALAMAR

by June 8, 2023In 2023, Mixmag is celebrating 40 years of documenting dance music and club culture. In this interview, Craig Seymour speaks to Jeffrey Daniel of Shalamar

CRAIG SEYMOUR | 18 MARCH 2023

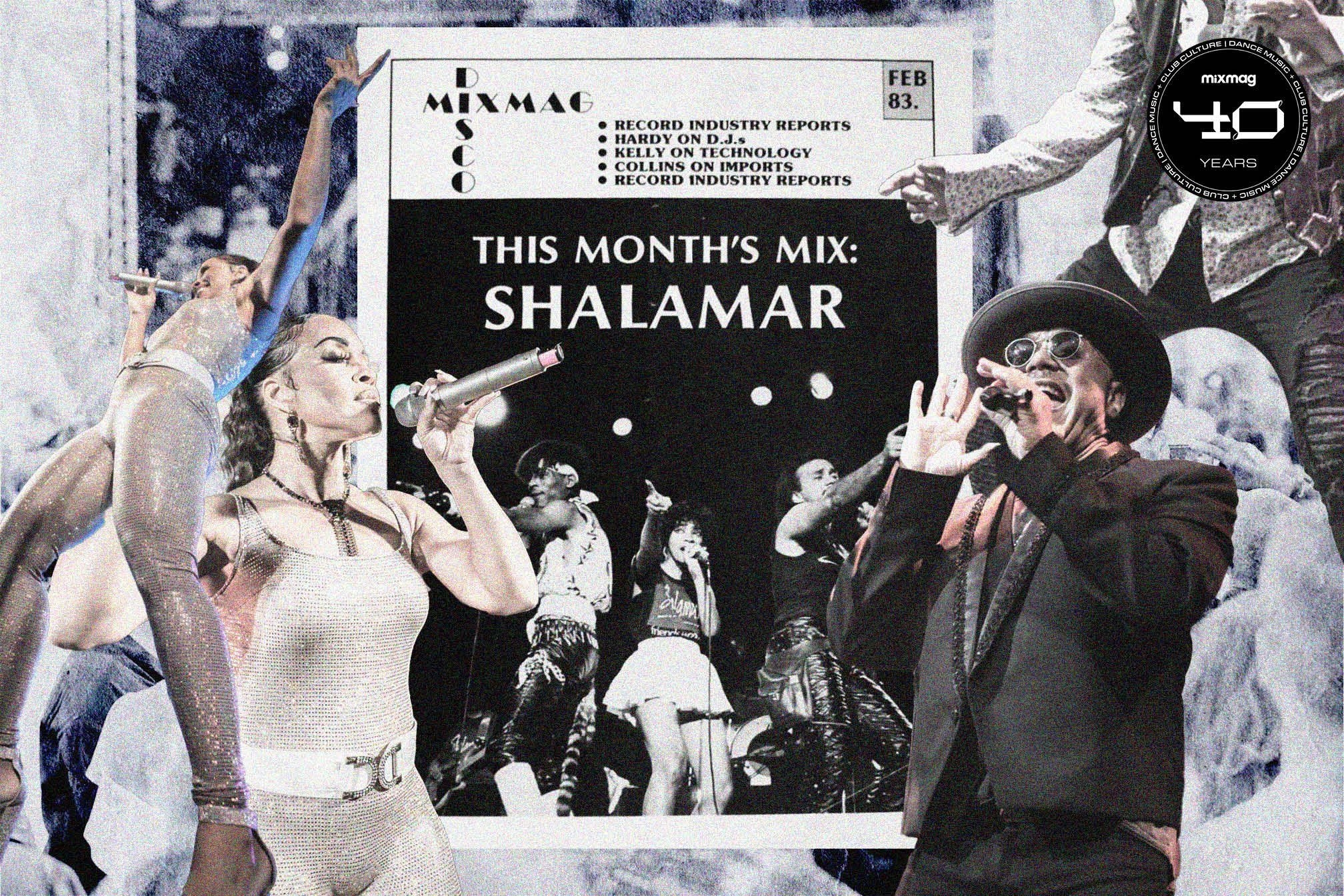

In February 1983, a 16-page black-and-white zine aimed at DJs was distributed by the Disco Mix Club mailing service, starring disco group Shalamar on the cover. This marked the birth of Mixmag, which was published regularly in this format ahead of its official launch as the first dance music magazine in 1989. This year we’ll be celebrating 40 years of Mixmag documenting electronic music and club culture with plenty of exciting plans in store. First up: an interview with our debut cover star Jeffrey Daniel of Shalamar.

Shalamar were in a jam. It was 1982, and the group’s single, the urgent groove ‘A Night To Remember’, was climbing the UK pop charts. Top Of The Pops wanted the Los Angeles-based trio–then consisting of vocalist Howard Hewett and former Soul Train dancers Jeffrey Daniel and Jody Watley–to appear on the show. But Watley was pregnant at a time before popstar mothers-to-be struck a ‘Buffalo Stance’ on national TV like Neneh Cherry or headlined the Super Bowl halftime show like Rihanna.

Shalamar’s label SOLAR chose to send Daniel to the UK — not to sing or lip-sync but simply to dance to the song. “The whole thing was unprecedented,” Daniel said in an interview to commemorate Shalamar’s appearance on the first ever Mixmag cover in February, 1983, coinciding with the group’s own forthcoming ‘Friends’ 40th anniversary tour with Carolyn Griffey–daughter of SOLAR founder Dick Griffey and disco star Carrie Lucas–standing in for Watley.

On Top Of The Pops, Daniel, wearing his hair in a straightened pageboy, popped, locked, and gestured like a b-boy Marcel Marceau as he acted out the song’s lyrics about getting ready for a memorable night on the town. Then, during the song’s funky bass breakdown, Daniel moved in reverse across the floor in a move he called the “backslide” and Michael Jackson would name the “moonwalk” one year later. This move made Daniel a star overnight, earning him a spot in the Paul McCartney film Give My Regards To Broad Street and the Andrew Lloyd Webber roller skating musical Starlight Express.

On the strength of Daniel’s performance, Shalamar became one of the UK’s top-selling acts of 1982, alongside such New Romantics, synth-popsters, and Britfunk-a-teers as Spandau Ballet, ABC, Yazoo, Junior, and Imagination. This streak of success was short-lived, though. In 1983, Daniel, Watley, and Hewett disbanded due to a myriad of personal, creative, and business issues. But the impact Shalamar made is undeniable for the almost unique way the trio mixed edgy new wave style, slick post-disco beats, state-of-the-moment dance movies, and strong yet sweet gospel-schooled vocals. (Daniel, Watley, and Hewett all have church backgrounds. Daniel grew up as the godson of gospel legend Rev. James Cleveland, who has influenced a range of artists from Aretha Franklin to James Blake.)

We talked to Shalamar’s Jeffrey Daniel, once married to R&B vocal powerhouse Stephanie Mills, about his religious upbringing, the queer influence on Soul Train and disco, the dance style “whacking,” considered by some to be California’s answer to voguing, working with the late Jermaine Stewart, and much more.

Is it true that Soul Train had a strong queer presence?

Going back to the ’70s, about 90% of the guys were gay. It was a world of their own. It wasn’t about being accepted or not being accepted. It was what it was. And I loved it. I would just be dying laughing. There was a lot of shade thrown around.

I guess it was an extension of the gay disco scene.

A lot of people do not understand the evolution that got dance music from disco to hip hop to where it is now. They aren’t aware that disco started in the gay clubs because it was a place for these guys to go where they would not be discriminated against. It was their thing. They’re the ones who chose songs like ‘Never Can Say Goodbye’ by Gloria Gayner, the Eddie Kendricks songs ‘Keep On Truckin’ and ‘Boogie Down’, Donna Summer’s ‘I Feel Love’, and ‘Theme From Shaft’ by Isaac Hayes. They took these songs and made them theirs. I’m not sure a lot of people understood or respected where the music was coming from.

Tell me about the queer dance style called “whacking.” In the book The Hippest Trip in America: Soul Train and the Evolution of Culture and Style, author Nelson George describes whacking as “[isolating] body parts…[moving] through space like summer fans in church ladies’ hands, with great speed and an exaggerated femininity…”

It was originally called punking. But when [Soul Train dancer Tyrone “The Bone” Proctor] was teaching it to me, he was like, “You got to whack the arm. You got to whack that head. You got to whack that to the beat.” And I said, “Ah…” So we started calling it whacking.

What’s the key to a good “whacking?”

First, it’s the attitude. If you don’t have the attitude, don’t even start. It’s the attitude, then the movement

It seems like you were very comfortable with the dominant queer presence on Soul Train. Did that come from your background in the Black church, which is known to have a large gay presence?

Being exposed to the gay community at [Rev. Cleveland’s Cornerstone International Baptist Church] kind of prepared me.

The vibe in a lot of Black churches is “don’t ask, don’t tell” when it comes to being gay. How would you know that someone was gay in the church?

What brought it to my knowledge was, from time to time, you’d shake somebody’s hand, and one of their fingers would tickle your palm [laughs].

How did Rev. Cleveland react when you signed up to be a member of a disco group?

I said, “James, I got a contract.” And he opened up a diatribe on me: “Are you a fool? Are you stupid? Why didn’t you bring it to me first? Did you let a lawyer see it?” Of course, I didn’t have a lawyer [laughs].

I understand what he was talking about now, but back then, I was like, “Why is he so angry?” I thought he’d be happy that I’m in the industry. But he understood the pitfalls. He understood the tricks. He understood the things that were waiting for me that I had no idea of.

Shalamar is infamous for line-up changes. Is it true that in the early days, management thought about replacing Jody Watley because they didn’t know she could sing?

Yes. so we started training Jody’s vocals. Jody loved Barbra Streisand back then; that was around the time of A Star Is Born and ‘Evergreen’. She loved that music. So, we would put on a Barbra Streisand record, and I’d say, “O.K., sing this.” And she would do it so quietly. I’d say, “O.K., now, just do it louder.” And I’d keep going, “O.K., do it louder. Do it louder.”

That’s how they teach you to sing in church, right?

There you go.

The other Soul Train dancers doubted her abilities as well.

The divas–and I’m not talking about the women divas–were like: “Why in the hell is this girl in the group when we wanted to be there?” So we had our very first show at Disneyland, right? We rehearsed for it and put our show together. So we get there, and Oh my God, all those Soul Train people were sitting up front with smirks on their faces, waiting for Jody to flop. But Jody came out, and when she opened up her mouth, singing, they started jumping up and down, cheering her on. And the rest is her-story.

That wasn’t your only memorable Disneyland show. Didn’t Michael and Janet Jackson come to see Shalamar perform there?

So we’re performing at the Space Mountain Stage, and our road manager says, “Jeffrey, your student coming to see you perform.” I said, “My student? Who you talking about?” He goes, “Your student coming. Michael Jackson’s coming to see you perform.” I said, “Really?” Up until then, I did not know I was Michael’s favorite Soul Train dancer. And he brought Janet Jackson with him. You know, she’s little Janet Jackson. This is 1980. So they came to watch our live performance. And here’s some trivia. The stage where we performed would become [where Disney screened Michael’s 3D film] Captain EO.

One of the dances Michael wanted to learn was the “backslide”, which he called the “moonwalk”. Why did you name the dance the “backslide,” since “backslidin’” has such a negative connotation in the church?

Yeah, in church, when you backslide, you’re on your way to hell, burning in hellfire for all eternity [laughs]. But it was just a name that stuck because that’s what it was. You’re sliding backward. Michael called it the “moonwalk”, but it’s not walking. You’re sliding. It’s the backslide.

What’s the secret to a mean “backslide”?

Don’t walk. You have to slide. You do not take a step back. You push off the ground from your toes. You push yourself back, then slide. The moment you take a step, you’ve blown it.

Let’s talk about the “backslide” that changed the world, your appearance on Top Of The Pops in 1982 when you performed a solo dance to ‘A Night To Remember’. How did you prepare for the show?

I got in my hotel room. I had the ‘Friends’ cassette. I put it in my cassette player, and I got in front of the mirror and just put this little routine together based on me getting ready to go out for the night. The audience went crazy because they had never seen anything like it before. They had never seen body popping, to begin with. And they had never seen the backslide. People didn’t know what was happening. They thought like I had wheels on my shoes. They thought there was oil on the floor. They did not know how in the hell I was walking forward and sliding backward at the same time.

You were such a hit that you were invited back on the show–by popular demand–to perform the song again.

People say I broke Shalamar in the U.K. But you have to understand, if it wasn’t for Howard Hewett and Jody Watley singing lead on ‘A Night To Remember’,”if it wasn’t for what they did on that song, I never would’ve had the opportunity to be on Top Of The Pops. The music predicates the dance, but my performance just took it to a whole new level.

In the liner notes of your solo album ‘Skinny Boy’, you call your time in London “the most beautiful time of my life.” Why was it so special?

I remember walking around London, going around Piccadilly, and I’m like, “Man, I got a good feeling about this place.” It was so invigorating. The music scene was so original. Everybody was expressing themself. You had Bow Wow Wow, Culture Club, Fun Boy Three, Bananarama, Adam and the Ants…

And you would all hang out at Camden Palace?

Top of the Pops would air on TV on a Thursday night, and after Top of the Pops, boom, you got to go to Camden Palace. Steve Strange [of Visage] was hosting it. You’d find everybody there: The Belle Stars, Echo & the Bunnymen, Haysi Fantayzee, Marilyn, DJ Jeremy Healy… I met Tom Bailey of Thompson Twins, and we are still good friends today.

How did your U.K. experiences change Shalamar’s sound?

Tom Bailey and I used to meet up on King’s Road on Saturday afternoons just to have tea together and chat. We would talk about what he was doing with the synthesizer. Then I became friends with Thomas Dolby when I heard the song ‘She Blinded Me With Science’. I was taken away from the hardcore soul thing. I mean, that’s Shalamar’s core, but this new synth-pop thing was going on. [Producer] Leon Sylvers saw I was into that, so that’s how Shalamar started progressing our sound into ‘The Look’ album with songs like ‘Dead Giveaway’, ‘Disappearing Act’, and ‘The Now Club’.

Your time in London also affected Shalamar’s style.

When I came back to L.A., I said, “Guys, we got to stop wearing these matching costumes.” Jody was designing our costumes, and she did a very good job. But I said that era is over, and Jody understood it. She didn’t take offense. And so that’s when we started dressing more individually and putting on some funky stuff. New Wave was happening, and we wanted to catch that wave. We caught it and rode it through England, through Europe. But mainstream America didn’t pick up on it like that. The people in middle America were like, “What the hell is that?”

In addition to your dancing, you were known for your signature hairstyles, especially when you wore it shaved on the sides, long and straight in the front.

When I saw the punks on King’s Road, I thought this was so funky. So I went and had my hair shaved with the geometrical thing going to one side. I came back home to L.A., and people were like, “What in the hell happened to Jeff?” Because I’d had this perfect Afro. Everyone knew me by this Afro, and here I am with one side of my head shaved off and the other side long. And you know Black people, they speak their mind. One day, I was walking in Westwood, waiting at a traffic signal to cross the street, and this one Black guy walked up behind me and said, “Damn, did Stephanie Mills do that to you?” [laughs]

Rev. Cleveland also publicly disapproved of your hairstyle, telling the Sunday Times in 1985, “that new hairstyle of his—I don’t like it at all.”

He thought, “The devil done got a hold of my godson, and I’m trying to get him to heaven.” [laughs] No, he didn’t say it like that, but he didn’t understand because he didn’t know about the punk scene and the New Romantics. There was a culture behind it.

Jermaine Stewart worked with Shalamar during this time. What do you remember about him?

He was on the road with Shalamar. He started off as a valet and then eventually became a background singer. Jermaine Stewart is one of the funniest people I’ve ever met. That boy would have us cracking up day and night. He used to imitate these old church ladies. We’d be at a restaurant, and all of a sudden, Jermaine would start shouting like he was in church, speaking in tongues and stuff. And we’d be so embarrassed while Jermaine is catching the Holy Ghost in the restaurant because the chicken tastes good. There was no shame in his game.

Did you get the chance to see him before he passed?

I was staying in the Marina del Rey, and I called him and said, “Jermaine, how you doing?” He said, “My big brother, I gotta see you.” I gave him my address, but he wouldn’t come.

Then I get in touch with him again and said, “Jermaine, what’s going on?” I couldn’t understand why he wasn’t coming to see me until I found out he was suffering the effects of AIDS. I heard some of his hair was falling out. He did not want me to see him like that. He just didn’t want his big brother to see him like that.

You broke the news that you, Jody, and Howard were splitting up in a 1983 Melody Maker interview. You said you owed an explanation to the “British public” because they’d been “exceptionally good” to Shalamar. What do you remember about that time?

Melody Maker had already shot Shalamar for the cover, but I’m the only one that showed up for the interview. That interview was very therapeutic for me because it was the first one I did when I decided to leave. I broke down and cried because it was my first time verbally saying I am no longer in the group. I was in London shooting a movie with Paul McCartney, Give My Regards to Broad Street. I took the money from the movie and put myself into a flat. And I just decided to stay in London. I was still getting over the divorce with Stephanie Mills and all that stuff. I just wanted to just find a space where I could regain myself. I didn’t just leave Shalamar; I left America.

Since dancing has been such a big part of your life, tell me some of your favorite dance songs.

My favourite dance song would be something like Roger Troutman and Zapp’s ‘More Bounce to the Ounce’. Or Cameo’s ‘Shake Your Pants’ or ‘I Just Want To Be’. That’s what we were popping to.

What are your favourite disco songs?

Either ‘Do you Wanna Get Funky With Me’ by Peter Brown or ‘Devil’s Gun’ by C.J. & Co. One of my favorite songs was the New York Community Choir’s ‘Express Yourself’. That stuff reminds me of Tyrone Proctor and our whacking days.

You’re about to head out on tour to celebrate the 40th anniversary of ‘Friends’. What do you recall about the making of the album?

People would never guess that we shot the album cover in Jody’s living room. Jody was so into the fashion thing that she wanted us to be shot by a particular photographer who worked with Vogue magazine [David Zahner]. So they booked the photographer, and he flew out to L.A., but they failed to book a photo studio. Jody just said, “Come to my place. We’ll do it at my place.” We shot against a white wall in her living room. She had to take her pictures down and everything.

How do you want Shalamar to be remembered?

I think that question is already answering itself because we are a group from the ‘80s, and here we are in 2023, going strong. It’s a blessing, and I’m very honored to be part of that. There are Shalamar fans all over the world. We don’t even call ’em fans anymore. We call ’em friends.

Shalamar are touring the UK in 2023, get tickets here

Craig Seymour is an author, critic and photographer, follow him on Twitter